By John Wesley Karson & Jaz McKay

In the early 1970s, a tectonic shift roared through Nashville’s pristine halls, where the “Nashville Sound”—with its syrupy strings, glossy harmonies, and often cloyingly sentimental lyrics—had long held court. A cadre of fiercely independent artists, fed up with the cookie-cutter constraints, lit the fuse on a movement that would be christened “Outlaw Country.” This wasn’t merely a new subgenre; it was a full-on insurrection, a bold manifesto of artistic autonomy that sent shockwaves rippling far beyond the country music sphere, leaving an indelible mark on rock, punk, and the very DNA of musical creation.

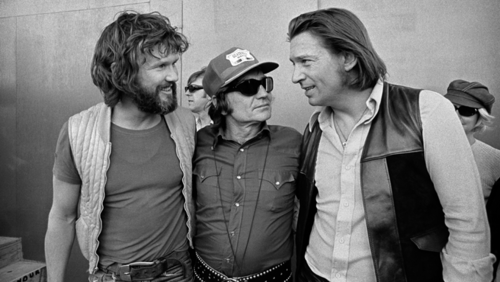

Before the outlaws rode into town, Nashville’s grip on country music was a stranglehold. Record labels called the shots, songwriters and performers were often kept in separate silos, and creative control rested squarely with producers chasing mass-market appeal. Artists like Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, and Johnny Cash, despite their varying degrees of success within this machine, felt their wings clipped. They hungered to pen their own songs, handpick their own bands, and inject a raw, unvarnished grit into a genre they believed had been scrubbed clean of its soul.

The immediate impact of Outlaw Country was a sledgehammer to its own genre. It demolished the rigid blueprint of what country music was supposed to be. The polished veneer was torn away, replaced by a sound that was jagged and unapologetic, weaving in threads of blues, rockabilly, and the rising tide of Southern rock. Lyrics turned deeply personal, diving into the messy realities of hard living, heartbreak, rebellion, and the working-class struggle with a stark honesty that hit like a gut punch. This authenticity struck a chord with audiences who were done with the fairy-tale version of life peddled by mainstream country. Albums like Waylon Jennings’ Honky Tonk Heroes and Willie Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger weren’t just records; they were declarations of intent, showcasing a newfound freedom in songwriting and production that thumbed its nose at Nashville’s old guard.

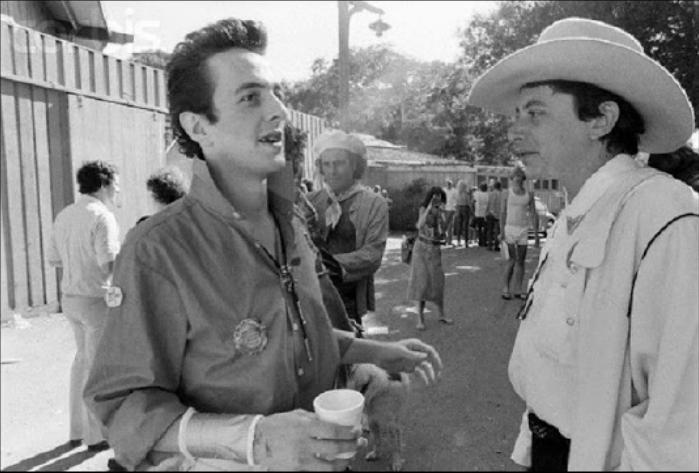

But the outlaws’ influence didn’t stop at the city limits of Nashville—it galloped far beyond, igniting fires in other genres. The late 1970s punk rock movement, for instance, found a surprising kindred spirit in the outlaws. Both were born from a visceral rejection of commercialism and artistic stagnation in their respective mainstream scenes. While their sounds couldn’t have been more different—punk’s snarling guitars and breakneck tempos versus the outlaws’ twangy, rootsy grit—their ethos was cut from the same cloth: a DIY attitude, raw energy, and a lyrical focus on societal outsiders, disillusionment, and defiance. The Clash’s Joe Strummer, a punk icon, famously forged a deep connection with Texas country outlaw Joe Ely, a friendship that epitomized this cross-genre camaraderie. Strummer, captivated by Ely’s rugged authenticity, invited him to open for The Clash during their 1979 U.S. tour. The two bonded over their shared disdain for corporate music machines, with Strummer even joining Ely on stage for duets like “I Fought the Law.” This punk-country crossover wasn’t just symbolic; it was practical. The outlaws’ insistence on controlling their own recordings, booking their own gigs, and writing their own material mirrored punk’s DIY ethos—bands like The Ramones and X were cutting their own records, booking dive-bar tours, and rejecting major-label gloss in the same way Jennings and Nelson fought Nashville’s stranglehold. This shared spirit of rebellion against the establishment made the outlaws and punks unlikely but powerful allies in the fight for artistic freedom.

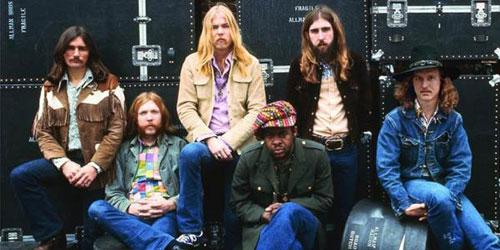

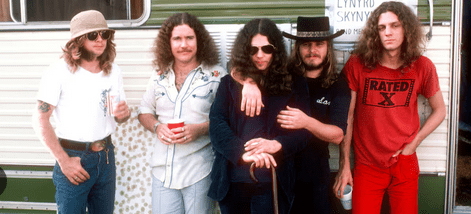

The outlaws’ rugged, individualistic image also left its mark on rock and roll, shaking up the early 70s’ parade of clean-cut pop idols. A grittier aesthetic took hold, with bands like Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers Band—firmly rooted in rock but sharing the outlaws’ swagger and storytelling sensibility—riding the wave. Genre lines started to blur, paving the way for the “country rock” boom that had been simmering but exploded into the mainstream on the heels of the outlaw movement. The Eagles, with their smoother sound, reaped the benefits of this newfound acceptance of country influences in rock, blending twangy harmonies with California rock in hits like “Take It Easy.” Even more direct descendants, like Gram Parsons with The Flying Burrito Brothers, leaned harder into the cosmic cowboy vibe, fusing country’s heartache with rock’s edge in a way that owed a clear debt to the outlaws’ trailblazing.

The long-term legacy of Outlaw Country lies in its unshakable commitment to artistic freedom. It proved that commercial success didn’t have to mean surrendering creative control. The outlaws showed that authenticity and a willingness to defy convention could not only resonate with audiences but could also redefine an entire genre. This lesson reverberated across the musical spectrum, inspiring alternative rock bands like R.E.M. to self-produce their early albums and hip-hop artists like OutKast to launch their own independent labels, all echoing the outlaw spirit of seizing control of their own destinies.

Today, the echoes of Outlaw Country are louder than ever in the rise of Americana and alternative country, genres that owe their very existence to the pioneers who dared to step outside Nashville’s lines. Artists like Jason Isbell and Sturgill Simpson carry the torch, blending traditional country sounds with contemporary sensibilities while emphasizing songwriting as a craft and tackling darker, more complex themes—addiction, loss, and societal fracture—with the same unflinching honesty the outlaws championed. The Drive-By Truckers, with their sprawling narratives of Southern life, channel the outlaws’ grit and storytelling, while Kacey Musgraves, though more polished, inherits their willingness to push boundaries, as seen in her genre-bending explorations of love and identity. Jamey Johnson’s raw, soulful voice and stripped-down production reject Nashville’s pop sheen, harking back to the outlaws’ insistence on keeping it real. The emphasis on authenticity, the rejection of manufactured gloss, and the courage to explore the shadows of human experience—all hallmarks of the outlaw legacy—continue to shape these modern movements, proving that the spirit of rebellion still thrives.

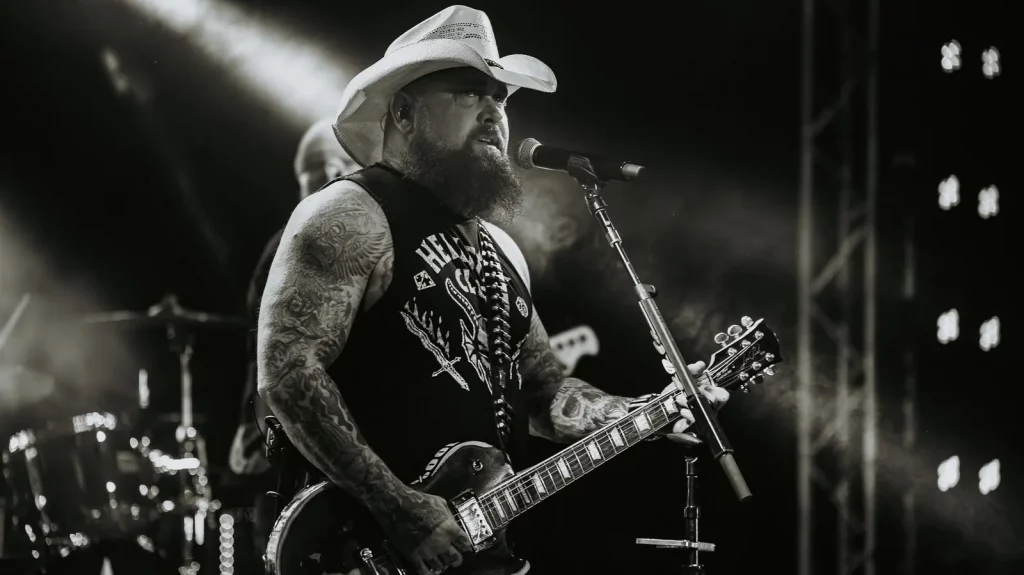

Then there’s Creed Fisher, a Texas-born outlaw country artist, channels the rowdy edge of Hank Williams Jr. with a gritty, unapologetic sound that’s steeped in the traditions of hard-living, blue-collar country music. His songs, like those on albums such as Whiskey and the Dog and Rednecks Like Us, blend honky-tonk swagger with a rebellious streak, echoing Hank Jr.’s “I don’t give a damn” attitude through anthems of patriotism, heartbreak, and working-class pride. Fisher’s raw vocals and storytelling—often drawing from his own rough-and-tumble life, including a failed marriage and years as a minor league football player—carry the same defiant energy as Bocephus, whether he’s belting out a barroom banger like “High on the Bottle” or a reflective ballad like “This Town.” With a knack for capturing the wild, unfiltered spirit of Southern life, Fisher’s music resonates as a modern-day nod to Hank Jr.’s rowdy legacy, proving he’s a force in the outlaw country scene.

In conclusion, Outlaw Country was no mere 1970s blip—it was a defining moment in music history, a revolt against artistic shackles that reshaped not just country music but the broader musical landscape. By championing authenticity, independence, and a raw, honest sound, the outlaws didn’t just revitalize their own genre; they empowered artists across genres—from punk rockers to Americana troubadours—to take the reins of their creative vision. The spirit of rebellion and genuine expression they unleashed continues to echo through the music of today, ensuring that the outlaws’ legacy will soundtrack generations to come.